Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

– Arthur C. Clarke

Planting seeds

Wireless networking has always felt like magic to me. Two computers talking to each other with no shared base just feels special. Thus, it was no surprise that I took several courses on wireless networking in my Computer Science Master’s degree. It just made sense.

I wasn’t disappointed with the basic courses, covering systems like WiFi, 3G and hearing commercial pitches for 4G/LTE and WiMax. But my imagination was really sparked when I did the course on wireless mesh networking. The vision of large amounts of systems talking to each other without depending on any infrastructure, this felt like science fiction to me.

During the course we studied many existing systems – such as AODV, ODMRP and SMAC – and were challenged to critique them and propose improvements. This has been one of the best courses I have followed during my Master’s. I was simply mesmerized. Another course focused on using these wireless networks to autonomously monitor environments: wireless sensor networks.

During this time I took regular walks on my university’s campus and I would often lie for hours in the grass, looking at the clouds pass. Then, one day, a glider from the nearby airfield came circling above my head at low altitude. Another one joined.

A thought involuntarily cross my mind: “What if we could map the structure of thermals in real time with a wireless sensor network?”. And thus, the subject for my Master’s thesis was born…

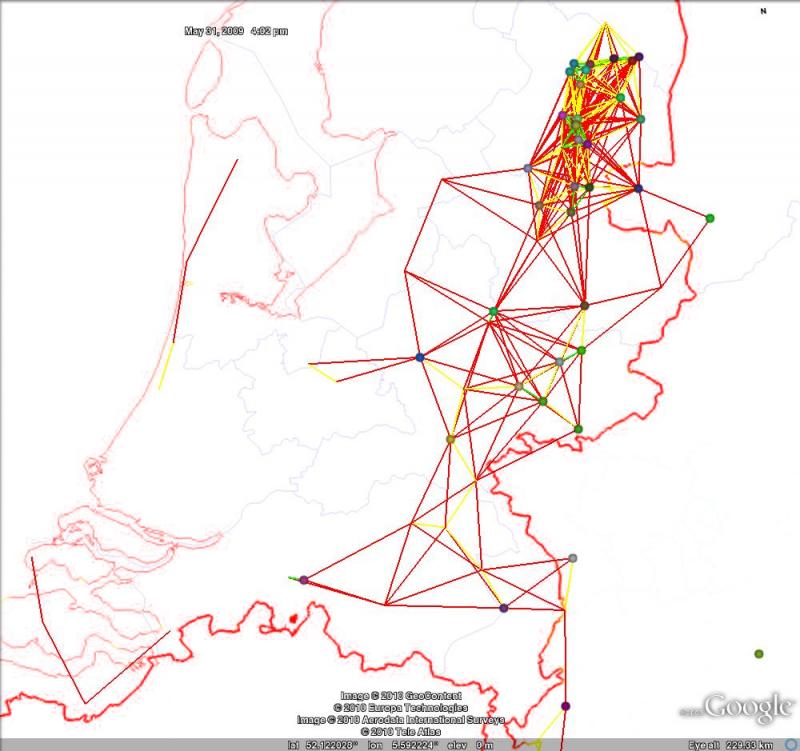

Master’s Thesis and a paper

I was able to convince the Pervasive Systems research group to let my do my Master’s thesis on the concept of “Wireless Mesh Networking for Gliders”. During my 9 months of research I selected the X-Bee Pro 868 transceivers has my hardware of choice. With a range of 40 kilometers, I expected they would be a good choice despite the low bandwidth. And since FLARM had already received exemption from the ground-only usage for the 868MHz band, I figured I could use them too. I used many IGC files to simulate what good days and bad days would look like in terms of connectivity. The potential is there, but routing data over a Wireless Mesh Network was harder than I could handle, especially since end-to-end connectivity between two gliders was rare. I designed a protocol based on epidemic routing, where nodes forward data based on probability rather than a strategy.

Meeting my heroes at OSTIV

Although my solution worked “okay” – I could deliver 80% of all data – my paper was accepted at the 2010 OSTIV conference in Szeged, Hungary. And since my university’s policy was to pay the expenses for attending any conference that accepted your paper, I got myself a free trip towards the World Gliding Championships in Szeged! I met many of the famous constructors: Loek Boermans, Mark Maughmer, Gerhard Waibel and Johan Bosman. They were all extremely welcoming and a lot of fun to hang out with! I presented my paper and received a prize for best (only) student submission. I had a blast.

Right after the conference I started working and had very little time to work on my project. I realized that there is an inherent chicken-egg problem in wireless mesh networking: you need others to pass your data along, and very few people are willing to be the first buying such a system. Also, the problems in efficiently carrying data from glider to glider persisted.

But there was also good news: OGN launched! Although coverage at the time was not great, it was a start. There was also live tracking by SkyLines, which worked over 3G. At first I thought both systems were too limited in their coverage. From experiments during several tows to 1200 meters during aerobatic courses, I learnt that coverage stopped at around 600 meters above ground. This improved, but I didn’t know it….

A revelation

…until I decided to perform another experiment. Since I had been running a backup for the SkyLines project, I had access to their database. And this database included the tracking information. I could see that 97% of all position reports arrived within 1 second! That meant that in 97% there was very likely a connection between the glider and the internet! This included flatland such as The Netherlands and the Alps. I figured my assumptions about connectivity were false, that it didn’t make any sense to continue working on the hard problems of wireless mesh networking and decided to just use 4G. I bought a 4G modem and started testing with it, and connectivity was indeed great.

Although this sadly removed any need for wireless mesh networking for gliders, it did free me to pursue the next step: figuring out what to measure and share it. More on that in a separate post…