Since I’ve not posted anything for… a long time now, I thought it was time for some updates. A lot has happened, and I think it’s time to talk about that.

New glider

In the past few years I started slowly looking for a glider to experiment with. The Hobbes project left me with a desire for more avionics experimentation. One of my personal conclusions of the project was that making something to build into a glider in just a day limits the options too much. Things like haptic feedback – which I knew was more optimal for Hobbes than acoustic feedback – was out of the question because of this.

In true “Test Driven Development” fashion, I had decided that I should make a large checklist of requirements for this next glider. I had bought my last glider, an Ls6b, based on my feelings alone. Don’t get me wrong, I still long for the incredible handling that the Ls6 had… but it wasn’t practical for me. At least not for the type of experimentation that I had in mind.

So I made a checklist with some requirements:

- The instrument panel of the glider should be easily accessible.

- The wings of the glider should be light enough to assemble it on any flyable day.

- The glider should have a tail-wheel, which saves my back during assembly and is nice during crosswind take-off.

- There should be ample space for batteries, baggage and equipment.

- The glider should fly easily enough to let people who just got their license fly on it and still have enough headspace to do something else.

- The glider should have a glass fuselage, so that I don’t struggle with adding antennas.

- The glider should have multiple sets of static ports, such that I can separate experimental equipment from mandatory equipment.

- The manufacturer should be supportive of experimentation with the aircraft, so I can ask for support if needed.

- The glider should perform well in weak weather, as this increases the chances I will assemble it and fly it.

- If at all possible the glider should have an engine, so I can make mistakes during testing and not land in a field.

Discus bT

In the end I settled on the Discus bT as a type. I flew the Discus bT of one of my friends about two years ago and tested some of the handling using the Idaflieg Zacherprotocol. I was pleasantly surprised by the handling. There is not much adverse yaw and the glider is overall easy to fly. The wings of the Discus bT are pretty light and it assembles easily.

During my visit of Aero Friedrichshafen in 2024 I had a nice chat with Tilo of Schempp-Hirth, and he was very supportive about my ideas for experimentation. That was a great pick-me-up and made me focus on the Discus bT more.

This particular Discus bT has a glassfiber fuselage (it also comes in a lighter all-carbon fuselage), which makes installing antennas easy. It contains three sets of static ports and two pitot tubes! This is ideal, because it allows me to put the experimental equipment on one set of pressure ports while critical instruments like the airspeed indicator, altimeter and transponder can be attached to another set. I can modify the experimental stuff as much as I want without affecting the critical instruments.

In the Discus bT the panel is very well accessible and since cables are not routed via the very front of the glider it is easier to add new cables. There is room next to the wheel for two standard 9aH batteries, and there is a mount for a 20aH battery for the engine right below the instrument panel.

This particular Discus bT contains no nose hook. Although that makes aero-tows a bit harder – especially with an aft center of gravity – it means that there is room for an extra 20aH battery in the nose. This means that I can also separate the power for any critical avionics, such as radio and transponder, from any experimental equipment.

Handling & Performance

I’ve flown some small cross-country flights in the glider and I enjoy both the handling and the performance of the glider. With the winglets it’s very docile around the stall and it carries its weight (400kg take-off weight) pretty well. On weak days I cannot out-climb my clubs Discus 2cT, but the glider can glide a long way with reasonable speed.

Next steps

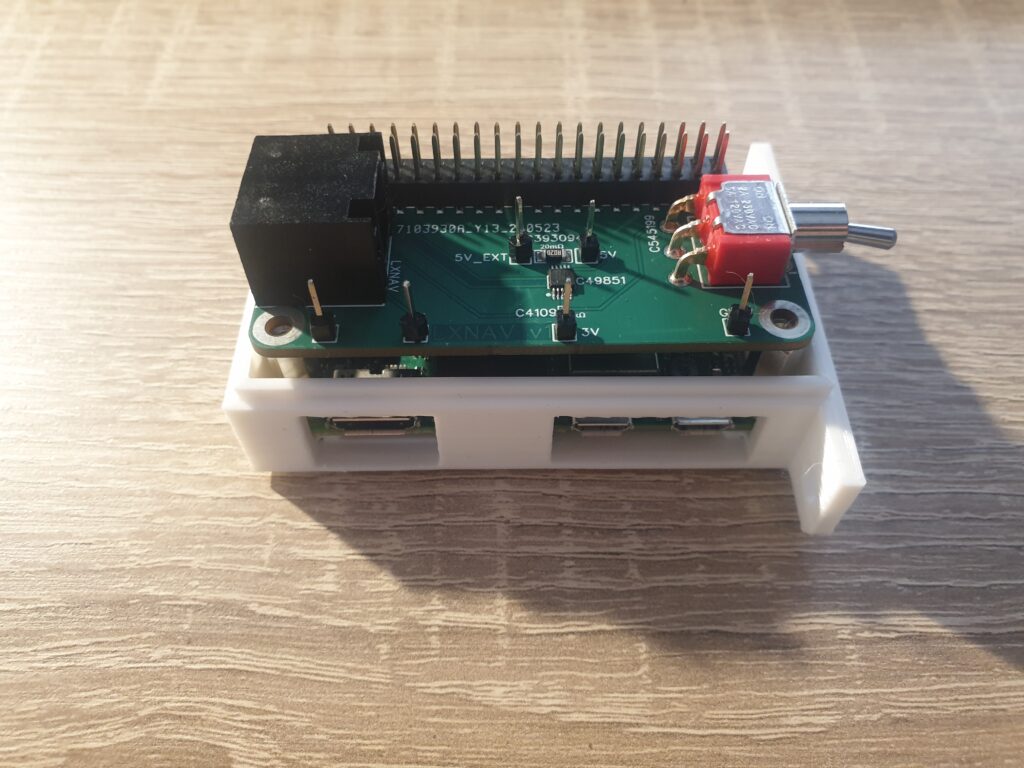

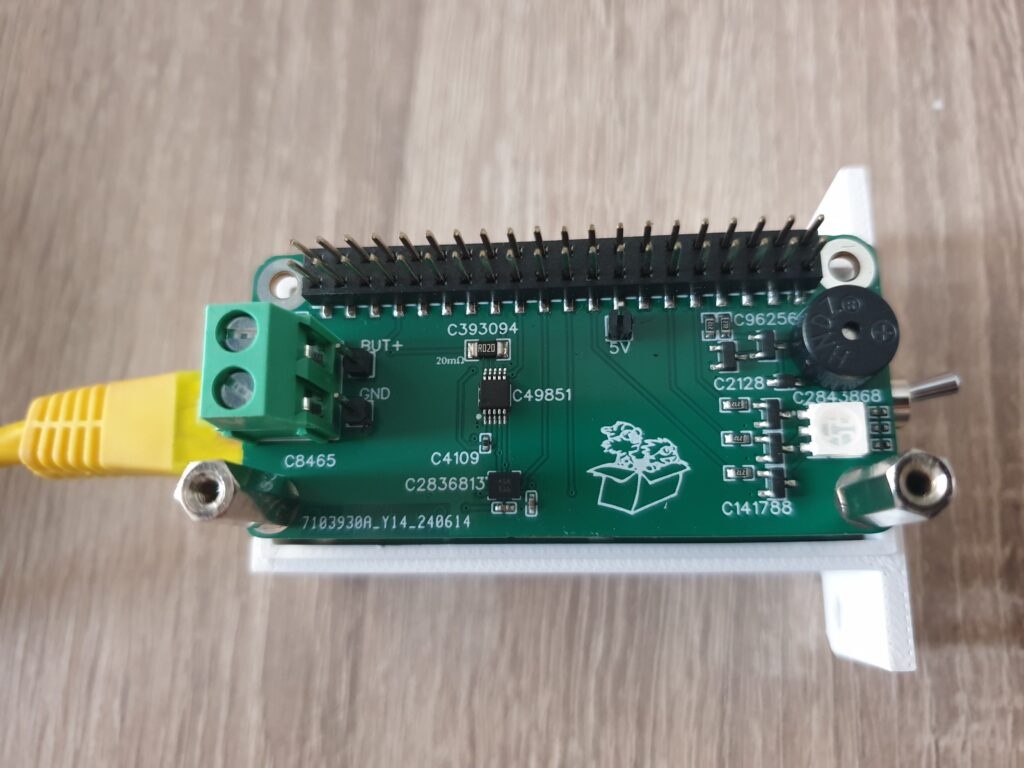

The Discus already has a pretty spacious panel, but I intend to clean it up a little bit. The separate radio and transponder that are present right now will be replaced by an Air Com, Air Control Display and Air Transponder. You can’t get any more compact than 3 instruments in one 57mm hole.

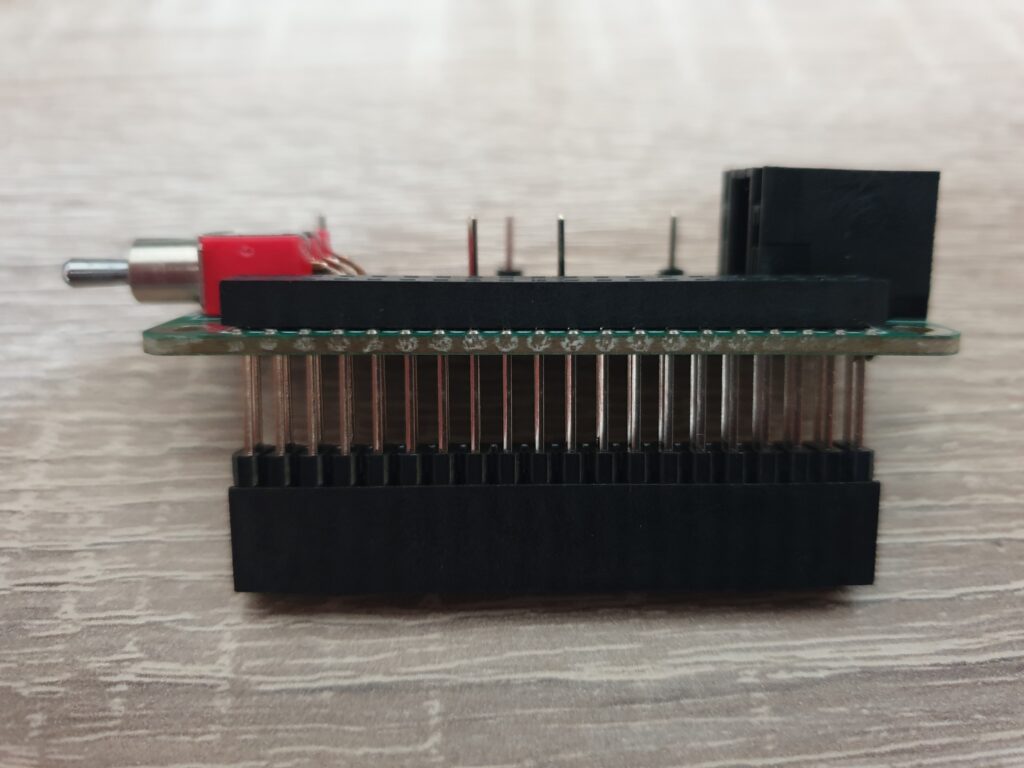

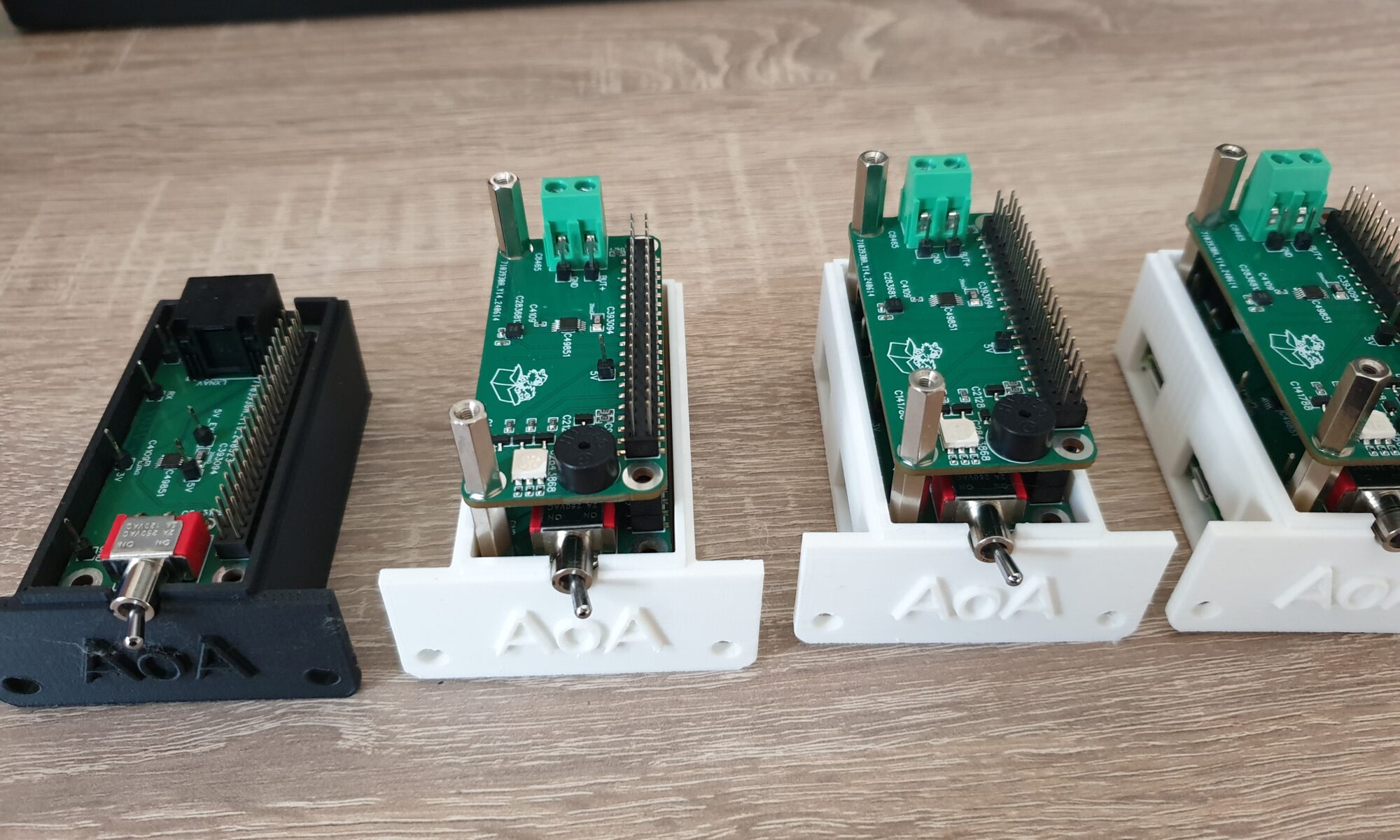

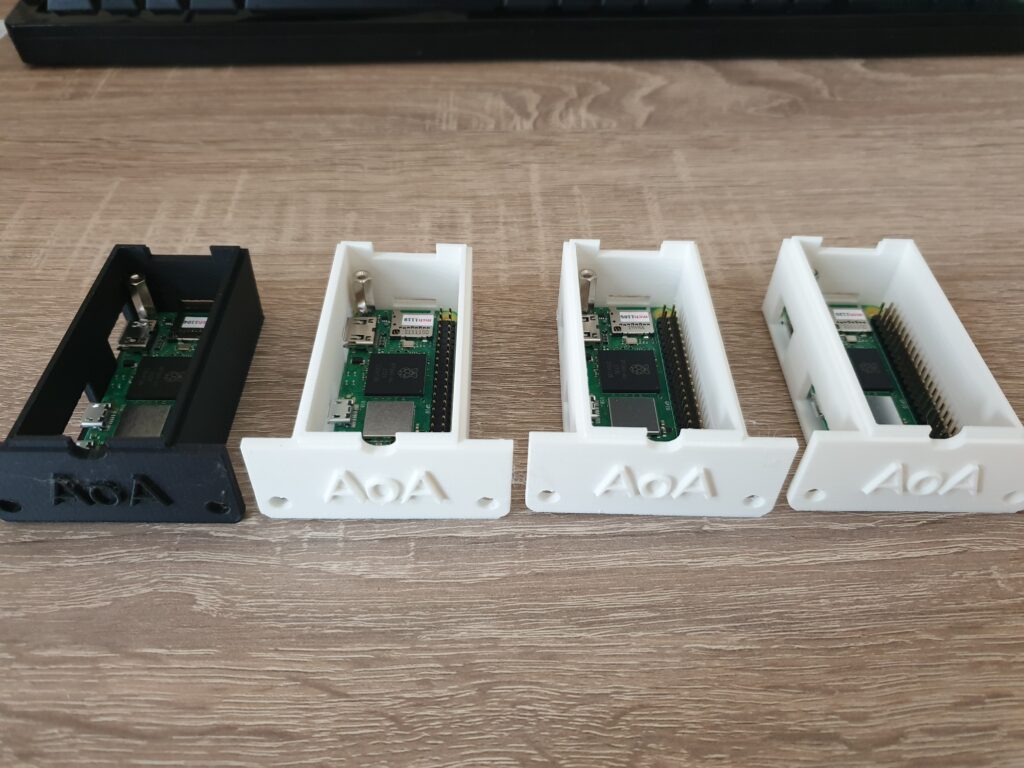

The center of the panel will feature a modular system such that experimental avionics can be quickly swapped out. These will have their own power source and will only use the pressure ports that are not connected to anything critical. A swap should only involve a Weight & Balance + Inventory list update. I’m currently figuring out what kind of regulations apply to the instrument panel of the glider and how I can ensure the safety of the glider with this modular system.

The glider will be fitted with an GPS-RTK set, which should give me a reliable heading and pitch indication.

Project

The first project for this glider will be the Pathfinder. The engine in the Discus bT allows me to experiment with potential algorithms without risking many outlandings. The modular instrument panel should allow me to experiment with ways of indicating the best strategy to the pilot.